How Dr. Katy Tudor & Dr. Minal Patel helped develop the Spatial Genomics Platform at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

Impact at a glance: This blog highlights how researchers built a dedicated spatial transcriptomics team at the Wellcome Sanger Institute. Learn how they’re leveraging their expertise to increase throughput and reduce costs, as well as how 10x Genomics has helped make it easy to incorporate spatial transcriptomics into their work.

From the early 1990s and the Human Genome Project, to the more recent work with the Human Cell Atlas Project and beyond, the Wellcome Sanger Institute has been instrumental in groundbreaking work on how genetics influences health and disease. Now, they’re adding a powerful new approach to their toolkit: spatial transcriptomics.

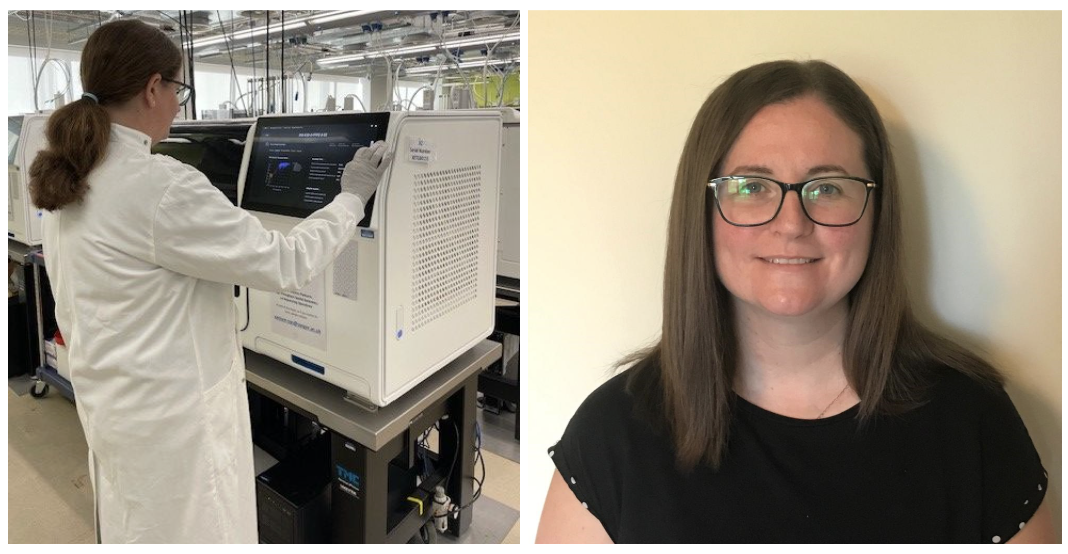

Dr. Katy Tudor, a Technical Specialist and key member of the Spatial Genomics Platform (SGP) at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, plays a central role in coordinating these initiatives in close collaboration with faculty teams across the Institute. Working alongside colleagues, such as Dr. Minal Patel, Spatial Operations Manager at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, who leads the coordination and optimization of spatial genomics workflows, the SGP team is dedicated to enhancing throughput through the application of cutting-edge spatial transcriptomics technologies. Their recent progress was showcased at the 10x Genomics Paris Core Summit, where Dr. Tudor was invited to present on the team’s advancements. Following the event, she kindly participated in a Q&A to share insights into the team's ongoing work and future directions.

Read on to see how she and her team are using these tools in their core facility, how they’re scaling up with these technologies, and the novel ways they’re increasing throughput and reducing costs of spatial techniques in their lab.

Can you describe your current work?

Our lab operates as a core facility, supporting a wide range of research-focused projects (none of which are diagnostic in nature). Many of these are rooted in large-scale initiatives, such as the Human Cell Atlas Project, which aims to build a comprehensive biological map of all human cell types. Over time, we’ve evolved to become the spatial genomics experts at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, working in close partnership with faculty teams across the institute. This transformation has been made possible through significant support and collaboration with the Cellular Genomic Faculty Programme, which has played a key role in helping us establish ourselves as the dedicated Spatial Genomics Platform within Sanger. Together, we’re enabling cutting-edge spatial transcriptomics across a diverse set of biological questions and projects.

One recent project we've had is using bacterial spike-ins to look at patients with cystic fibrosis on the Visium and Xenium platforms with Dr. Josie Bryant’s team. It worked quite nicely, both because of the bespoke spike-ins using the Visium CytAssist and the post-Visium runs on Xenium. Both of the workflows work together well, and the data is looking good.

Another big project we've been involved in is with Professor Muzz Haniffa’s team at Wellcome Sanger Institute. They're running the largest study in the UK to monitor treatment response in the skin from patients with severe eczema treated with biologics and oral therapy. They've tested both Xenium v1 and Xenium Prime 5K assays, both with and without multimodal cell segmentation, to see which of the panels best fits their needs. We’ve also contributed to Dr. Omer Bayraktar’s glioblastoma work that combines single cell, spatial, transcriptomic, epigenetic, and genomic profiling data spanning multiple regions of the brain across three or four years.

Our spatial work on the thymus spans different developmental stages, and some of the more recent projects we've worked on have included pancreas, liver and kidney. These projects have also involved your spatial technologies and are leveraging AI models to make predictions about diseases.

That’s a truly impressive body of work; congratulations!

Thank you! A lot of the initial work was discovery and seeing what these technologies can do, while our more recent projects were looking at various aspects of disease. Now, a lot of our current projects are trying to do things on a larger scale. So not just 1 or 2 samples, but 10, 20, 30. It’s certainly resulted in an increased demand for our team, which is good!

So, what sparked you and your team’s interest in spatial?

Spatial combines a lot of what I focused on in my PhD, like molecular histology and immunofluorescence. Normally, you’re either a histologist, a molecular biologist, or a bioinformatician because they’re all quite niche areas. That’s why I like spatial: it combines multiple different skillsets.

I felt histology was a dying art, but, with spatial technologies, it’s been accelerated to the forefront of science with the plexity and multiomics you can get with the Xenium platform.

As for our team, we started off as part of the Human Cell Atlas project with a more single cell focus, diversifying into spatial transcriptomics to meet the scientific needs of the institute. A lot of our team had a lot of histology experience, including myself. So, we combined those strengths and became the spatial experts at the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Bioinformatics is sometimes seen as challenging for people interested in spatial transcriptomics. In your experience, has 10x Genomics helped make that easier for you?

The support that 10x gives the Wellcome Sanger Institute and other people, especially with the analysis software, has really simplified things. I know people who run their own analysis pipelines, but the 10x bioinformaticians are always very willing to help. The support side of things from 10x has always been great. The institute also has a plethora of bioinformatics experts that collaborate with 10x Genomics to analyze the spatial data generated by the core team.

Have there been any challenges you’ve faced incorporating spatial transcriptomics?

As for the biggest challenges: analyzing large datasets. Imagine dealing with 30 different donors, where you’ve got tissue blocks, slides, tubes, sequencing data, and trying to combine, track, and link it all has been quite a headache at times. The size of the data involved in both storage and analysis is always a challenge.

You gave a recent presentation at the core summit on how your lab’s increasing throughput and reducing costs. Can you touch on how you’re accomplishing this?

We make use of the safe stopping points in the Visium protocol so that we can confidently batch things up and group things together. So, for the bigger requests, we can stain the slides in bulk and image them, use that safe stop point after the imaging, then hold the rest for the following week. It lets the day one of the following week be quite short, which frees personnel up to do tasks like histology or analysis.

Normally, we run our stored slides on the Visium CytAssist over the course of three days: two half-days and one full day. On day one and day three we have one person doing the batching and then, on day two, the CytAssist day is transferring analytes between the slides and the tubes and running the machine. We have two people running them. It frees up people to do additional tasks so we can keep the throughput high.

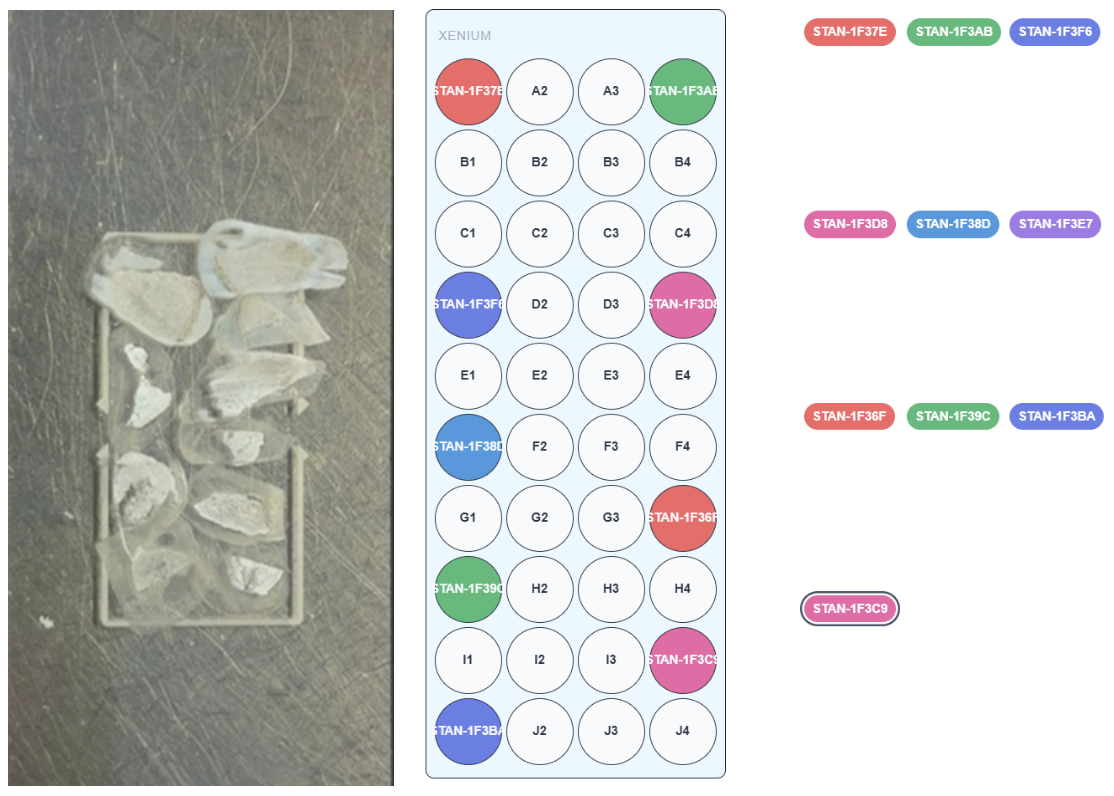

For Xenium, running multiple slides in parallel, as well as running multiple instruments, has significantly increased our ability to create large datasets.

Multiple instruments also help speed things up, but our team plays a big role since they’re all cross-trained on the Visium CytAssist, Xenium assays, and histology. So, our team can pivot from one technique to another depending on our current needs. It massively reduces turnaround time and the time to impact in delivery of science across the institute.

Has your group experimented with tissue placement to maximize tissue area on either Xenium or Visium slides?

On Visium, I think the most we've really done is two to three sections on a Capture Area. On the Xenium, I’ve personally sectioned up to about 12 different blocks onto one slide. It wasn't a tumor microarray (TMA) on a single block, so it was a bit like playing Tetris, but TMAs are going to be incorporated at some point.

What made you choose 10x Genomics for your spatial work?

Our team was involved with spatial transcriptomics before 10x Genomics, when you had to make all the reagents yourself. 10x streamlined it, optimized it, and made it a lot more reproducible and consistent in generating high-quality data.

When I joined, there was a lot of single cell data generation in flight at the Wellcome Sanger Institute (and still is), and spatial transcriptomics supplemented it. But we also found that spatial transcriptomics could be a discovery tool in its own right, because some of the genes we identified through Visium weren’t initially spotted with the single cell data. But once they’d analyzed the Visium spatial data, they went back to the single cell level and found those niche cells they were looking for. People always think spatial is a complement for the single cell data, but [it] is rapidly emerging to be an entity in its own right.

Previously, single cell data was validated using 4-plex RNAscope within our core team, however, as the number of plex increased, the quality and consistency of the data was unable to support the scientific questions. So when Xenium came out and it let us go from four genes of interest to hundreds or thousands of genes, it was a huge benefit for our work.

Our team has had great support from 10x Genomics. The relationship we’ve built over time has been collaborative; we’ve gotten help from technical support, engineers, Field Application Scientists, and the R&D team over in your headquarters. I think that support network really helps.

So, looking toward the future: what would your core like to see more of?

One topic we always get asked about is three-dimensional whole-mount staining. There’s a lot of organoid work going on, so something that can analyze tissue more than 10 microns thick—or capture organoids in and of themselves—would be really appealing.

Thank you so much for your time!

You’re quite welcome.

Following Dr. Tudor’s blueprint for spatial biology at scale

Single cell spatial transcriptomics technologies are driving new insights that would have been unthinkable even a decade ago—but making those insights accessible requires tools that are not just powerful, but high-throughput and cost-effective.

In this interview, Dr. Tudor highlighted her and her core team’s blueprints for accomplishing these aims with tools from 10x Genomics and how researchers can get the most out of the Xenium and Visium platforms.

Keep an eye out to learn more in an upcoming webinar with Dr. Tudor. In the meantime, see how other researchers are drastically reducing per-sample costs in single cell spatial transcriptomics, or start exploring what the Xenium platform can do for you, and see how it’s helping fellow researchers.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. We'd like to thank Dr. Tudor for her contributions!

About the author: